“The person who's birthing has to go very deep into their own thing, and nobody can do it for them. But having a strong tether – I feel so honoured to be a part of that.” - Emily Ekelund, Registered Midwife

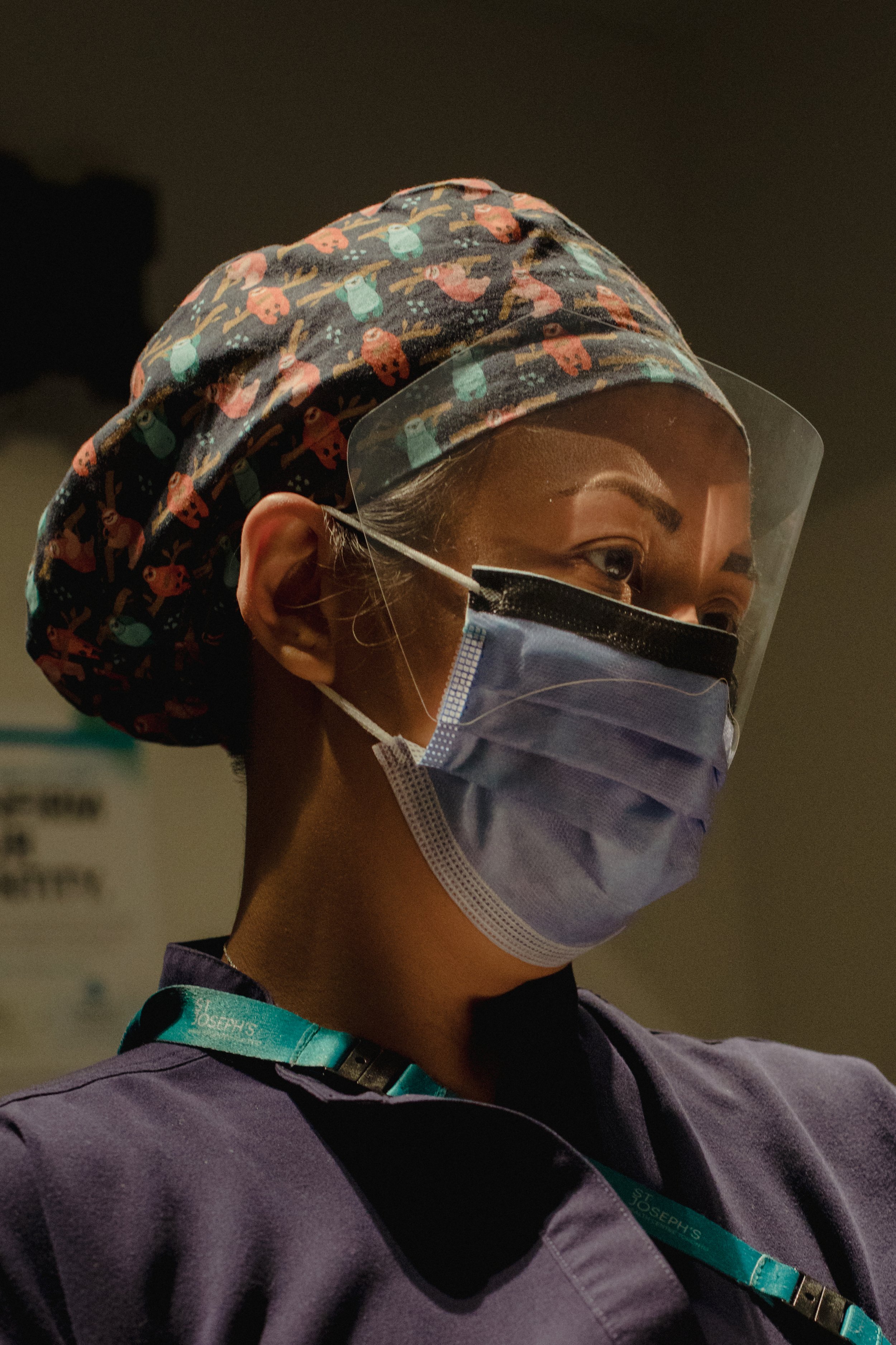

As provinces across the country contend with an ongoing shortage of family physicians and an overwhelmed hospital system, a growing chorus of medical experts who specialize in pregnancy care and childbirth say midwives are in a unique position to alleviate some of that strain on the system while providing high-quality care.

In 2021, nearly 1,900 midwives provided care during 48,420 births, up from 40,939 in 2019. In Ontario, nearly one in five births (18 per cent) was supported by a midwife in 2022, up from 16 per cent in 2015-16.

“Midwifery has become a major provider of maternity care,” said Douglas Wilson, a former president of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. “The reality is that they are low-risk or normal pregnancy providers, on par with family doctors.”

Midwives are health professionals who provide care during pregnancy, labour and during the postpartum period, typically for women who have low-risk pregnancies. Unlike obstetricians, midwives typically visit individuals in their homes and can facilitate either home births or hospital births.

But some midwives say they aren’t being properly utilized and can’t work to their full potential because they aren’t always recognized or compensated in the same way as other health professionals. Jasmin Tecson, a former president of the Association of Ontario Midwives, said there are a number of factors involved, notably the lack of a provincial plan to better incorporate midwifery services into hospitals and ensure midwives are being paid fairly. “I really feel we aren’t being leveraged appropriately,” Ms. Tecson said.

There have been some recent changes to allow midwives to deliver more care. This month, Ontario announced that they will now be able to administer routine vaccines and prescribe and administer a range of new medications, including those to treat nausea and help manage labour.

Ms. Tecson and others point to a unique program at Markham Stouffville Hospital that is a model for high-quality care. The Alongside Midwifery Unit (AMU) offers all the benefits of midwifery care – house calls, 24-hour on-call support and a homelike birthing environment – combined with access to immediate obstetrical support and other hospital interventions if required.

For many, the unit is a happy medium between a hospital and a home birth, said Abigail Corbin, patient care manager with the AMU, which was the first of its kind in Canada when it opened in 2018.

Rooms at the AMU feature birthing pools, therapy balls and other equipment. Once the baby arrives, parents can use the double Murphy bed in each room.

“It’s basically a birthing centre in a hospital,” Ms. Corbin said. “Some births go from being completely fine to deteriorating quite quickly. The benefit of our unit is we are right beside labour and delivery.”

During the pandemic, the AMU began providing patients who didn’t have a family doctor with ongoing support during the postpartum phase. The Family and Baby Clinic has become a staple of the program, Ms. Corbin said. “We thought that would be just a temporary program during COVID,” she said. “In fact, the need is only growing. We have people calling from other communities looking for help because they have no family doctor.”

The clinic saw 1,318 families in the 2022-23 fiscal year, Ms. Corbin said, providing essential services such as weight check-ins for newborns and jaundice follow-up visits. “That program is only funded for two full-time midwives,” she said. “We have been very creative in how to see as many people as possible with just a little bit of funding.”

PUBLICATION:

The Globe and Mail - The Labour Crunch

The Globe and Mail - How midwives are taking on more demands, sacrifices to keep working during the COVID-19 pandemic